The “yield” of a metal component is a fundamental mechanical property that defines the transition point from elastic to plastic deformation. Understanding this point is critical in engineering design, material selection, and failure prevention.

1. Fundamental Concept: The Stress-Strain Curve

The yield behavior of a metal is most clearly understood from its Engineering Stress-Strain Curve, obtained from a tensile test.

Elastic Region (Point O to Yield Point): In this region, the metal deforms when a load is applied but returns to its original shape upon unloading. The deformation is reversible and follows Hooke’s Law (Stress ∝ Strain). The slope in this region is the Elastic Modulus (Young’s Modulus), a measure of the material’s stiffness.

Yield Point (The Critical Transition): This is the specific stress level where the material begins to deform plastically.

Plastic Region (Beyond Yield Point): Beyond this point, the deformation becomes permanent. If the load is removed, the material will not return to its original dimensions; it will have a permanent “set.”

2. Defining and Measuring Yield Strength

For most metals, the transition from elastic to plastic is not a sharp, single point. Therefore, several definitions are used to quantify the “yield strength”:

Yield Point (for some steels): Some low-carbon steels exhibit a distinct Upper Yield Point and Lower Yield Point. This is an exception rather than the rule.

Offset Yield Strength (Proof Stress – Most Common Method): For the vast majority of metals (e.g., aluminum, stainless steel, brass), the curve is smooth. The yield strength is defined using an offset method.

A line is drawn parallel to the elastic portion of the stress-strain curve, but offset by a standard amount of plastic strain (commonly 0.2% or 0.002 strain).

The stress at the point where this line intersects the stress-strain curve is designated as the 0.2% Offset Yield Strength (σ_y). This is the value reported in material data sheets.

Yield Strength by Total Strain: Sometimes, the yield strength is defined as the stress at which the total strain reaches a specific value (e.g., 0.5%).

3. The Microstructural Mechanism: Dislocation Motion

The macroscopic yielding of a metal is a direct result of microscopic events:

Elastic Deformation: At low stresses, atomic bonds are stretched, but the atoms do not permanently change neighbors.

Onset of Yielding (Plastic Deformation): The stress becomes high enough to cause the movement of dislocations (line defects in the crystal lattice).

Yielding occurs when dislocations begin to slip (move) on specific crystallographic planes.

The yield strength is essentially the stress required to initiate and sustain large-scale dislocation motion across the grains of the metal.

4. Key Factors Influencing the Yield Strength of a Metal Component

The yield strength is not a fixed value for a given metal; it is highly dependent on several factors:

Material Composition: Alloying elements can significantly increase yield strength by creating solid solutions, forming precipitates, or changing the crystal structure (e.g., adding carbon to iron to make steel).

Microstructure:

Grain Size: According to the Hall-Petch relationship, a smaller grain size leads to a higher yield strength. Grain boundaries act as barriers to dislocation motion.

Precipitates & Second Phases: Hard particles within the grains (precipitation hardening) are extremely effective at blocking dislocations, dramatically increasing yield strength (e.g., in aluminum alloys or nickel-based superalloys).

Work Hardening (Strain Hardening): As a metal is plastically deformed, dislocation density increases, and they become entangled. This makes it progressively harder to cause further deformation, thereby increasing the yield strength after the initial yielding. This is the reason a metal feels harder after being bent back and forth.

Heat Treatment: Processes like annealing (softening), quenching, and tempering are used to control the microstructure and precisely tailor the yield strength of a component.

Temperature: Yield strength generally decreases as temperature increases. At high temperatures, atoms have more energy, and dislocations can move more easily (a phenomenon known as creep becomes significant).

5. Practical Importance in Engineering Design

The yield strength is arguably the most important property in mechanical design:

Prevention of Permanent Deformation: Engineers design components so that the maximum expected service stress is below the yield strength (with a safety factor). This ensures the part will not be permanently deformed during its normal operation.

Safety Factor = Yield Strength / Maximum Working Stress

Material Selection: For a given application, a material is chosen based on its yield strength, weight (specific strength), cost, and corrosion resistance. For example, the aerospace industry uses high-strength aluminum and titanium alloys for their excellent strength-to-weight ratios.

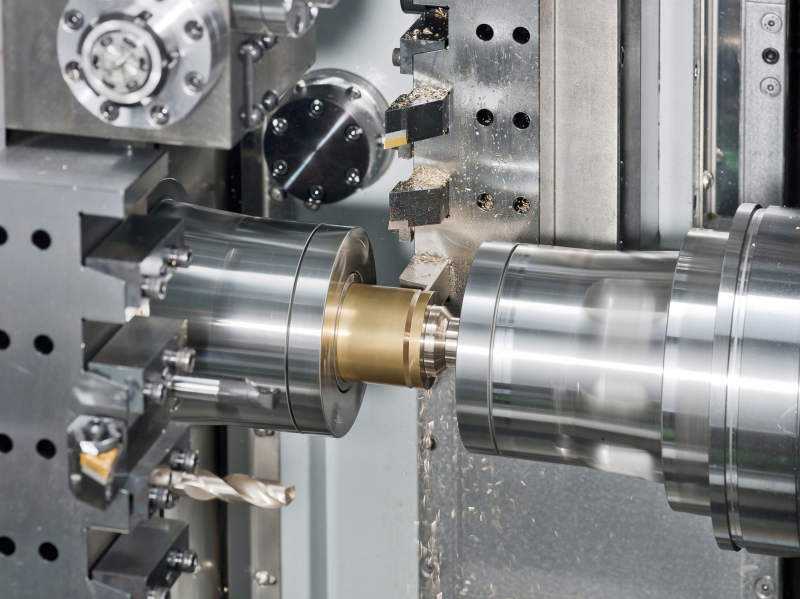

Forming and Manufacturing: Processes like forging, rolling, and stamping intentionally stress metals beyond their yield strength to plastically form them into desired shapes.

Summary

In conclusion, the yield of a metal component is the critical stress threshold that separates reversible, elastic behavior from permanent, plastic deformation. It is primarily defined as the 0.2% Offset Yield Strength, is governed by the motion of dislocations at the microscopic level, and is a variable property controlled by composition and processing. Its accurate determination and application are foundational to creating safe, reliable, and efficient engineered structures and products.