1. Carbon Steels

Carbon steels are the most widely used forging materials due to their excellent strength, ductility, and cost-effectiveness. They are classified by carbon content:

Low-Carbon Steel (Mild Steel, <0.3% C): Excellent ductility and weldability; used for general-purpose components, automotive parts, and structural shapes.

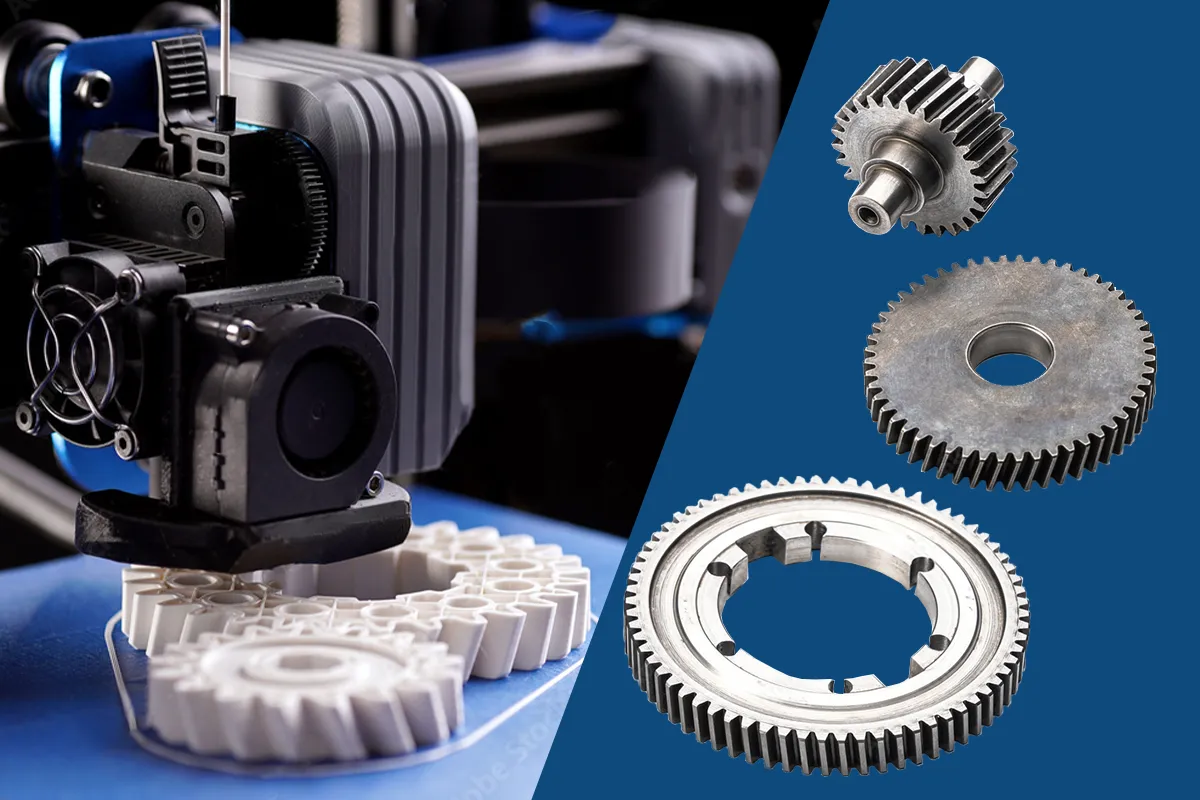

Medium-Carbon Steel (0.3% – 0.6% C): Balanced strength and toughness; commonly forged into crankshafts, gears, bolts, and connecting rods.

High-Carbon Steel (0.6% – 1.0% C): High hardness and wear resistance; used for cutting tools, springs, and wear-resistant components. Requires careful heat treatment.

2. Alloy Steels

These steels incorporate alloying elements (e.g., chromium, nickel, molybdenum, vanadium) to enhance specific properties.

Chromium-Molybdenum (Cr-Mo) Steels: High temperature strength and creep resistance; essential for power generation components (turbine shafts) and high-pressure piping.

Nickel-Chromium-Molybdenum (Ni-Cr-Mo) Steels: Exceptional toughness and hardenability; used for large, critical parts like aircraft landing gear, gears, and heavy-duty shafts.

Stainless Steels: Corrosion-resistant alloys.

Austenitic (e.g., 304, 316): Non-magnetic, excellent corrosion resistance and formability. Forged into valves, fittings, and chemical processing equipment.

Martensitic (e.g., 410, 440): Magnetic, can be hardened by heat treatment. Used for cutlery, blades, and pump shafts.

Ferritic (e.g., 430): Moderate corrosion resistance, magnetic; used for automotive exhaust components.

3. Microalloyed Steels

Also known as High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) steels, they contain small additions of niobium, vanadium, or titanium. They gain high strength through controlled cooling after forging, often eliminating the need for subsequent heat treatment. Widely used in automotive components (crankshafts, connecting rods) and structural parts.

4. Aluminum Alloys

Forged aluminum alloys offer an excellent strength-to-weight ratio, good corrosion resistance, and high thermal/electrical conductivity.

2XXX Series (Al-Cu alloys, e.g., 2014, 2024): High strength, used in aerospace structures and military applications.

6XXX Series (Al-Mg-Si alloys, e.g., 6061, 6082): Good combination of strength, weldability, and corrosion resistance; common in automotive wheels, bicycle frames, and marine fittings.

7XXX Series (Al-Zn alloys, e.g., 7075): Very high strength, used in highly stressed aerospace components and performance sporting goods.

5. Titanium Alloys

Known for exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, excellent corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. They are challenging to forge due to high temperature requirements and sensitivity to contamination.

Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5): The “workhorse” alloy, used in aerospace (airframe, engine components), biomedical implants, and high-performance automotive parts.

Commercially Pure Titanium (Grades 1-4): More formable and corrosion-resistant, forged into chemical processing equipment and marine components.

6. Nickel-Based Superalloys

These alloys retain exceptional strength, creep resistance, and oxidation resistance at extremely high temperatures (often above 70% of their melting point).

Examples: Inconel 718, Inconel 625, Waspaloy.

Applications: Critical for hot-section components of jet engines and gas turbines (turbine disks, blades, casings), and in high-temperature chemical processing equipment.

7. Copper Alloys

Forged for their superior electrical/thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance, and antimicrobial properties.

Copper: Electrical components, busbars.

Brass (Cu-Zn): Good machinability and appearance; used for valves, fittings, and architectural hardware.

Bronze (Cu-Sn, Cu-Al): High wear resistance and fatigue strength; forged into bearings, gears, and marine propellers.

8. Magnesium Alloys

The lightest structural metals (⅓ lighter than aluminum). Forged for applications where weight saving is critical. They require careful handling due to flammability risks at high temperatures.

Example: AZ31B, AZ80A.

Applications: Aerospace components, lightweight housings, and high-performance automotive parts (steering wheels, seat frames).

Key Considerations in Material Selection for Forging

Forgability: The ease with which a material can be deformed without cracking. Generally, low-carbon steels and aluminum alloys have high forgability, while high-alloy steels and superalloys are more difficult.

Grain Flow: Forging refines the metal’s grain structure and orients it to follow the part’s contour, creating a continuous “grain flow.” This significantly enhances fatigue resistance and toughness compared to machined or cast parts.

Heat Treatment: Most forged components undergo subsequent heat treatment (e.g., quenching and tempering, annealing, aging) to achieve the desired final mechanical properties (hardness, strength, toughness).

Performance Requirements: The choice is driven by the service conditions: required strength, operating temperature, corrosion environment, weight limits, and fatigue life.

In summary, the selection of a forging material is a critical engineering decision that balances forgeability, cost, post-forging treatments, and the final performance requirements of the component under its intended service conditions. The forging process itself is valued for producing parts with superior mechanical integrity and reliability.