Injection molding is a high-precision, high-efficiency manufacturing process used to produce complex, dimensionally stable plastic parts in massive volumes. It is the dominant process for mass-producing identical thermoplastic and thermoset polymer components, ranging from tiny gears to entire automotive bumpers.

- Core Principle

The fundamental principle is simple: Melt plastic, inject it into a mold under high pressure, cool it, and eject the solid part. However, the execution involves precise control of numerous interdependent parameters.

2. Key Components of an Injection Molding Machine

A standard machine consists of two main units:

The Injection Unit: Heats and plasticizes the raw material (pellets or granules).

Hopper: Feeds material into the barrel.

Barrel & Screw: The screw rotates to convey, compress, melt, and homogenize the plastic. It then acts as a plunger to inject the melt.

Heater Bands: Precisely control the temperature along the barrel zones.

Nozzle: Connects the barrel to the mold.

The Clamping Unit: Holds the two halves of the mold closed with immense force.

Mold (Tool): The custom-designed, hardened steel (or aluminum) cavity that defines the part’s shape. It consists of a fixed “A” side (attached to the stationary platen) and a moving “B” side (attached to the moving platen).

Tie Bars, Moving Platen, and Clamping Cylinder: Generate and withstand the clamping tonnage to keep the mold closed against injection pressure.

3. The Injection Molding Cycle (Step-by-Step)

A single cycle, typically lasting from 10 seconds to a few minutes, involves four primary phases:

Phase 1: Clamping

The clamping unit closes the two mold halves with high hydraulic or electric force (measured in tons), ensuring the mold is securely locked before injection.

Phase 2: Injection

The plastic pellets are fed from the hopper into the heated barrel. The rotating screw transports them forward, where friction and heater bands melt them into a viscous fluid. Once a sufficient “shot” of melt accumulates in front of the screw, the injection phase begins:

The screw stops rotating and acts as a ram.

It pushes the molten plastic at high speed and pressure (injection pressure) through the nozzle, sprue, runners, and gates into the sealed mold cavity.

This phase is critical for filling the entire cavity before the melt starts to solidify.

Phase 3: Cooling & Packing

Packing/Holding: Immediately after filling, additional pressure (holding/packing pressure) is applied for a short time. This forces more material into the cavity to compensate for material shrinkage as it begins to cool, preventing sink marks and ensuring dimensional accuracy.

Cooling: The molten plastic inside the cooled mold cavity solidifies. Cooling time is the longest portion of the cycle. Efficient cooling channel design within the mold is vital for productivity and part quality.

Phase 4: Ejection

The clamping unit opens, separating the mold halves.

Ejector pins (built into the mold) advance to push the solidified part(s) off the core and out of the mold.

The mold closes, and the cycle repeats automatically.

4. Critical Process Parameters (The “Recipe”)

Optimal part quality depends on the precise control and interaction of these parameters:

Temperatures:

Melt Temperature: Specific to the polymer (e.g., 200°C for PP, 280°C for ABS).

Mold Temperature: Affects surface finish, crystallinity, and cycle time (cooler is faster but can cause defects).

Pressures:

Injection Pressure: Fills the cavity (typically 500-2000 bar).

Holding/Packing Pressure: Compensates for shrinkage (~50-80% of injection pressure).

Back Pressure: Pressure on the screw during recovery, improving melt homogeneity.

Time:

Injection Time: A few seconds.

Holding Time: A few seconds.

Cooling Time: The majority of the cycle.

Cycle Time: Total time from clamp close to clamp close again.

Speeds:

Injection Speed/Flow Rate: Determines how quickly the melt fills the cavity. Affects molecular orientation, weld lines, and surface appearance.

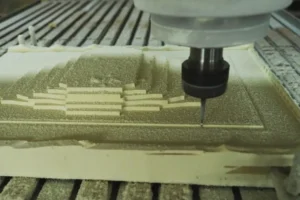

5. The Mold (Tool)

The mold is a masterpiece of engineering and the single most expensive element. Key features include:

Cavity & Core: Form the external and internal shapes of the part.

Runner System: Channels that deliver melt from the sprue to the cavities.

Gate: The small, critical opening where melt enters the cavity. Design (pin, edge, submarine) heavily influences part quality.

Cooling Channels: Circulate water or oil to control mold temperature.

Ejection System: Ejector pins, sleeves, or stripper plates.

Vents: Tiny grooves to allow trapped air to escape, preventing burns or short shots.

Draft Angles: Taper on vertical walls to facilitate part ejection.

6. Materials

Primarily thermoplastics (can be re-melted): Polypropylene (PP), ABS, Polyethylene (PE), Polycarbonate (PC), Nylon (PA), Acrylic (PMMA). Some thermosets (cure irreversibly) and elastomers are also used.

7. Advantages & Disadvantages

Advantages:

Extremely high production rates.

Excellent repeatability and part-to-part consistency.

Low labor cost per part (highly automated).

Ability to produce complex geometries with high precision.

Minimal post-processing/finishing required.

Wide range of material choices and colors.

Low scrap rates (runners can often be reground and reused).

Disadvantages:

Very high initial cost for machine and mold/tooling.

Long lead times for mold design and fabrication.

Economical only for high-volume production (>thousands of parts).

Part design is constrained by the physics of the process (draft, wall thickness, etc.).

8. Common Defects & Troubleshooting

Process optimization (“process window development”) is key to avoiding defects such as:

Short Shot: Incomplete cavity filling. (Increase melt temp, injection pressure/speed).

Sink Marks: Localized depression on thick sections. (Increase packing pressure/time, improve cooling).

Weld Lines: Weak lines where melt flows meet. (Increase melt temp, adjust gate location).

Flash: Excess thin material on part edges. (Increase clamping force, reduce injection pressure, repair mold).

Warpage: Distorted part after ejection. (Improve cooling uniformity, adjust packing, modify part design).

9. Applications

Ubiquitous across all industries: automotive (dashboards, bumpers, light housings), consumer electronics (housings, buttons), medical (syringes, housings), packaging (caps, containers), consumer goods (toys, kitchenware).

In summary, injection molding is a cornerstone of modern mass manufacturing. Its success hinges on the perfect synergy of four elements: a well-designed part, a precision-engineered mold, the correct material, and a finely-tuned process recipe. Mastering this interplay allows for the economical production of vast quantities of intricate, reliable plastic components that define the modern world.